1031 Exchange

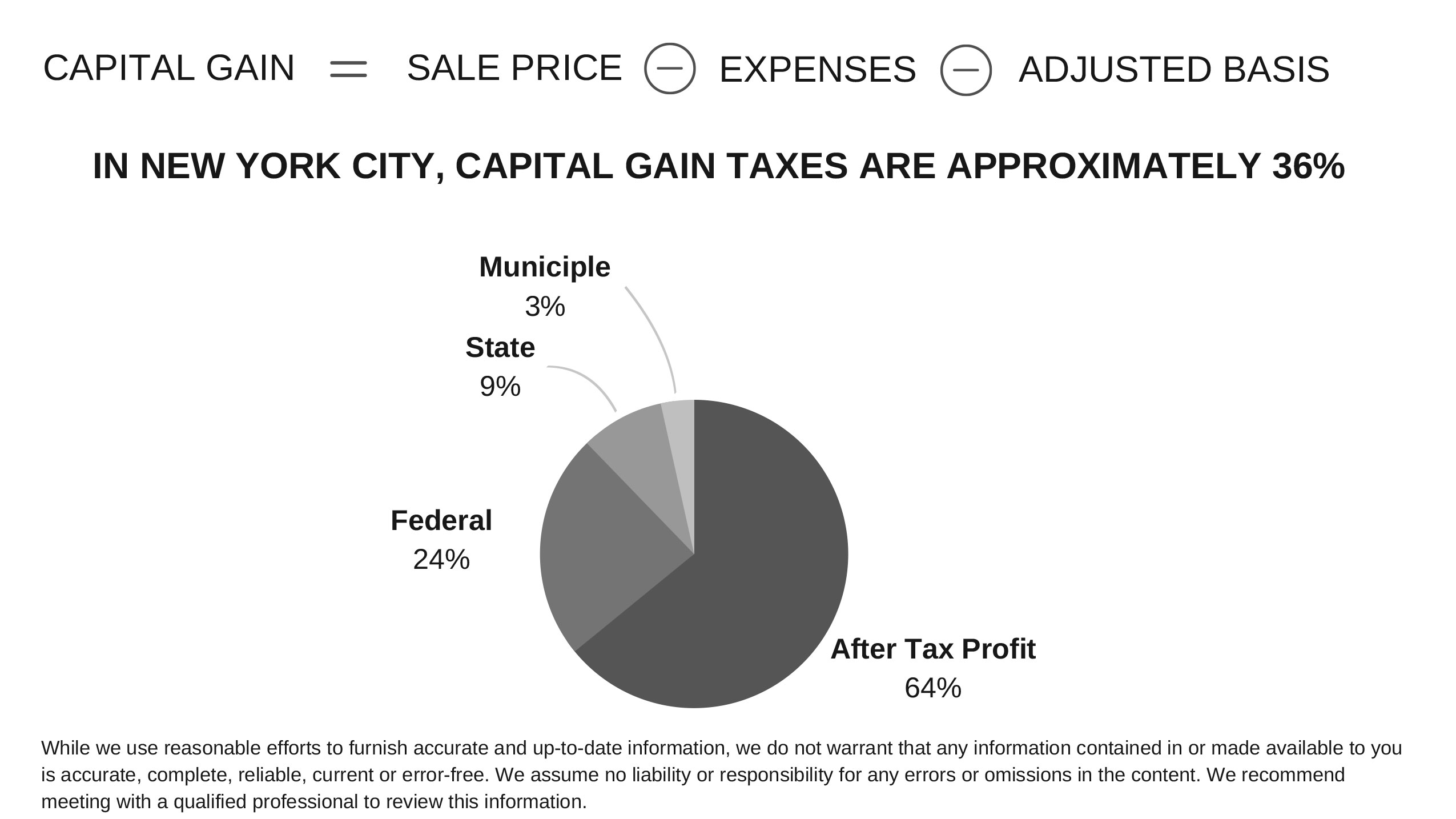

DIFFERING CAPITAL GAINS THROUGH A 1031 EXCHANGE

Capital Gains are the profits that occur as a result of the difference between the selling and purchase price of a property that are taxed. The amount can vary based on a number of considerations, such as whether or not someone is a resident of the United States, current condition of the property and the tax basis. Deductions from Capital Gains include the fees for the loan application, closing costs, and the points that were paid for the loan to get a lower interest rate for the mortgage. Thanks to Internal Revenue Code Section 1031, a properly structured 1031 exchange allows an investor to sell a property, to reinvest the proceeds in a new property and to defer all capital gain taxes. IRC Section 1031 (a)(1)

states:

“No gain or loss shall be recognized on the exchange of property held for productive use in a trade or business or for investment, if such property is exchanged solely for property of like-kind which is to be held either for

productive use in a trade or business or for investment.”

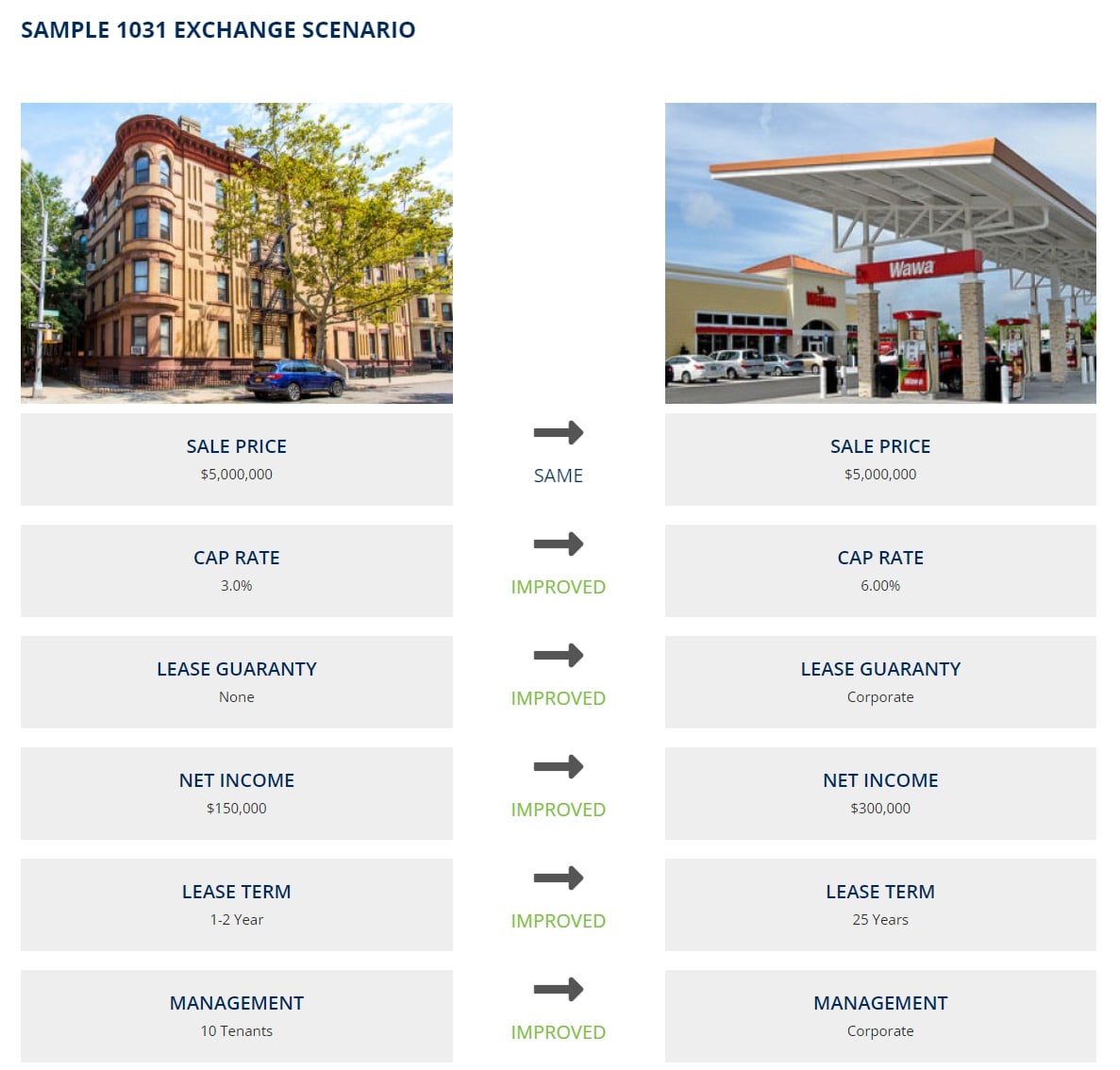

To put it simply, a 1031 exchange allows an investor to “defer” paying capital gains taxes on an investment property when it is sold, as long another “like-kind property” is purchased with the profit gained from the sale of the

first property. For example, perhaps you are investing in properties that are low-income and high-maintenance. You could exchange the high-maintenance investment for a low-maintenance investment without needing to pay a significant amount of taxes. Or perhaps you want to move your investments from one location to another without the IRS knocking. The 1031 Exchange makes this possible.

EIGHT THINGS TO KNOW ABOUT 1031 EXCHANGES

1. A 1031 isn’t for personal use.

The provision is only for investment and business property, so you can’t swap your primary residence for another home and defer all of the capital gains. If your primary residence is sold, a married couple can defer $500,000 and a single person $250,000, as a tax write off for capital gains.

2. But some personal property qualifies.

Most 1031 Exchanges are of real estate. However, some exchanges of personal property (say a painting) can qualify. Note, however, that exchanges of corporate stock or partnership interests don’t qualify. On the other hand, interests as a tenant in common (sometimes called TICs) in real estate do.

3. “Like-kind” is broad.

Most exchanges must merely be of “like-kind”–an enigmatic phrase that doesn’t mean what you think it means. You can exchange an apartment building for raw land, or a ranch for a strip mall, or a condo. The rules are surprisingly liberal. You can even exchange one business for another.

4. Qualified Intermediary.

Classically, an exchange involves a simple swap of one property for another between two people. You need a middleman (called a qualified intermediary) who holds the cash after you “sell” your property and uses it to “buy” the replacement property.

5. You can designate multiple replacement properties.

The IRS says you can designate three properties as the designated replacement property so long as you eventually close on one of them. Alternatively, you can designate more properties if you come within certain valuation tests. For

example, you can designate potential replacement properties as long as the fair market value of the replacement properties does not exceed 200% of the aggregate fair market value of all the exchanged properties.

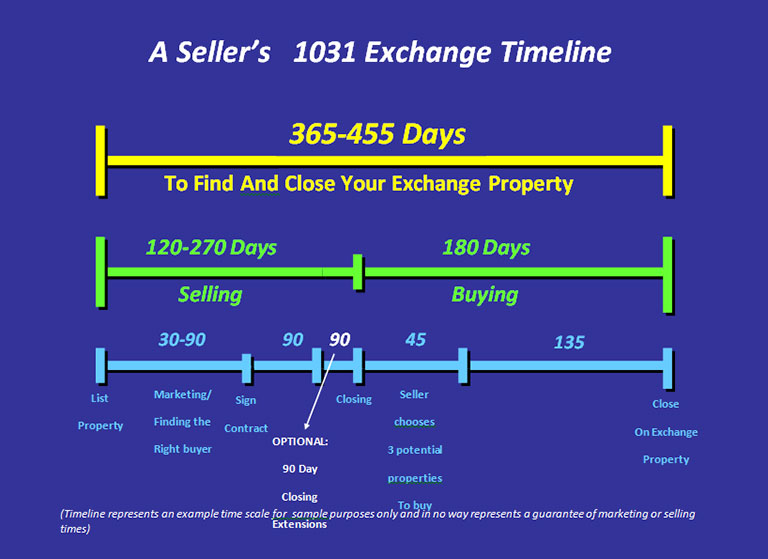

6. You must close within six months.

You must designate replacement property before 45 days after the closing and you’ll have 135 days left to close on the replacement property. You must close on the new property within 180 total days of the sale of the property. Note that the

two time periods run concurrently. That means you start counting when the sale of your property closes.

7. If you receive cash, it’s taxed.

You may have cash left over after the intermediary acquires the replacement property. If so, the intermediary will pay it to you at the end of the 180 days. That cash–known as “boot”–will be taxed as partial sales proceeds from the sale of your property, generally as a capital gain.

8. You must consider mortgages and other debt.

One of the main ways people get into trouble with these transactions is failing to consider loans. You must consider mortgage loans or other debt on the property you relinquish, and any debt on the replacement property. If you don’t receive cash back but your liability goes down, that too will be treated as income to you just like cash. Suppose you had a mortgage of $1 million on the old property, but your mortgage on the new property you receive in exchange is only $900,000. You have $100,000 of gain that is also classified as “boot,” and it will be taxed.

A Seller’s

TIMELINE

The key to making sure that you preserve the thousands of dollars you have earned with your investment property is to make sure that the sale and purchases are structured correctly. The way most people make money with real estate investments is due to the fact that they buy low and sell high. Selling high usually requires a marketing strategy by a real estate professional*, and buying low is easiest for buyers who are willing to act quickly. If done correctly, a 1031 Exchange allows you to do both of these things. The chart below is an example of the sale-thru-exchange timeline that I recommend to all clients who wish to carry out this transaction.

What is a like-kind exchange? (1031 Exchange)

Put simply, it is a technique for deferring gain on the sale of property by re-investing proceeds of sale in “like-kind” property. The theory is that if one does not cash out of an investment (having rolled over proceeds into new like-kind property), the economic gain has not been realized in a way that produces the cash to pay the tax, and so no tax should accrue.

Do I permanently escape tax?

No. The like-kind exchange rule is a tax-deferral technique. The new property purchased with the proceeds from the sale of old property has the same low tax basis as the old property. When the new property is later sold, the original deferred gain, plus any additional gain realized since the purchase of the new property, is subject to tax. Of course, one can sell the new property as part of another like-kind exchange and continue to roll over.

What is like-kind property?

In the context of real estate, it is easy. Virtually any real estate is like-kind to any other real estate (such as vacant land for a strip shopping center, an office building for an apartment building, etc.). Personal residences cannot be exchanged. Foreign property cannot be exchanged for U.S. property. Long term leases of real estate (30 + years) can qualify as real estate for purposes of an exchange; this is useful in the context of ground leases.

How is an exchange different than a sale and purchase?

Technically, the two legs of an exchange (the sale and the purchase) must be part of an “interdependent” transaction. In reality, there are just a few mechanical steps that are necessary to coordinate the sale with the purchase so that they are treated as an exchange. In the old days, the buyer of the old property had to go and purchase the new property for the taxpayer and then turn around and sell the new property to the taxpayer. With the use of so-called “qualified intermediaries” (discussed below), the buyer of the old property or the seller of the new property need not be involved (and may hardly know) of your exchange. (There is a technical requirement that other parties be notified that an exchange is occurring.)

What is a qualified intermediary?

A qualified intermediary is an independent agent that facilitates an exchange. The taxpayer’s attorney or accountant cannot be a qualified intermediary. Most intermediaries are affiliated with banks, trust companies or title companies. Using a qualified intermediary is one way of “safe harboring” an exchange. Essentially, the qualified intermediary takes an assignment of rights in the sale contract for the old property and the purchase contract for the new property. These are simple documents that the attorney fills out, along with a basic exchange agreement with the intermediary. Through these three documents, the intermediary is brought into the exchange and, subject to compliance with the timing rules discussed below, the transaction can qualify as an exchange rather than a taxable sale.

What about the money?

The most important role of the qualified intermediary is that it holds the proceeds of sale pending reinvestment in new property. The Internal Revenue Service takes the position that if the seller receives (or has direct or indirect use of or control over) the proceeds of sale, then there should be tax. By arranging for the qualified intermediary to hold the money, the taxpayer never receives the cash and therefore the transaction can be viewed as an exchange.

What are the timing rules?

Within 45 days of the closing on the sale, the taxpayer must “identify” the new property. The identification must be specific (such as the address of property or the make or model of a vehicle if one is exchanging a truck, for instance). For the possibility that the deal the taxpayer wants to do may fall through, the taxpayer may designate more than one property (generally up to three, or more than three if the total value of the new properties designated is less than twice the value of the property sold). One can even identify fractional interests in property that will be held in a legitimate co-tenancy (and not a partnership). Identification is made by sending the qualified intermediary written notice of the targeted new property.

When do I have to close?

One must close on one or more of the identified properties within 180 days of the date of closing on the old property. This is not 45 days plus 180 days. The 45 and 180 day periods run concurrently. The 180-day period is cut short if the tax return filing deadline comes up before the end of that period; one can get the full 180 days, however, by extending the time for filing the tax return.

How do I buy more time on the sale of my old property?

Contract sales do not work, since a contract sale is treated as a sale for tax purposes. What does work is a lease with an option where the buyer can take occupancy now but the closing is deferred. Or, you can do a so-called reverse exchange.

What is a reverse exchange?

As of September 15, 2000, reverse exchanges (when the new property is purchased before the old property is sold) are permitted. However, you must use a special “parking intermediary” to purchase and hold the new property until the old property is sold. The old property sale can be structured as a normal “forward” exchange where the proceeds are rolled over into the new property being “warehoused” or “parked” with the parking intermediary. The parking intermediary can hold the new property for up to 180 days.

What about newly constructed property?

One can trade into newly constructed property, but one cannot own the land on which the improvements are being built. The land must be owned by either the seller, the developer or a parking intermediary. If the taxpayer already owns the land, it can be sold to a parking intermediary or the developer. The seller or intermediary will contract to construct the improvements, and at the end of the 180-day period can convey the property (completed or partially completed) to the taxpayer to close out the exchange. This is usually a race against the clock to try to spend as many construction dollars as is necessary to complete the trade. One cannot prepay construction costs.

When you say proceeds need to be rolled over to avoid gain, is that all there is to it?

No. The essence of a trade is that one has not cashed out any part of the investment. One must trade up or even on price. And one must use all of the cash proceeds from the sale. Taking this altogether, the transaction is taxable to the extent that the purchase price of the new property is less than the selling price of the old property. And the transaction is taxable to the extent that there is cash left over with the qualified intermediary after the purchase of the new property (except that if the left-over cash is attributable to real estate tax prorations, security deposits or other prorations on the purchase of the new property; that money can often be taken off the table without creating tax). If one trades up or even in price and uses up all the cash, then the debt (comparing the mortgage on the old property to the mortgage on the new property) should be roughly the same or greater. If the debt goes down, there is potential tax unless more cash is put into the deal. One cannot borrow more on the new property as a way of trading up and taking cash out of the deal.

How do I get my equity out?

As mentioned above, one must trade up or even on price and use up all the cash. So while one can put more debt on the new property (if it costs more than the old property), one cannot refinance in the middle of the trade and take cash off the table. Typically, what is done is to leverage up the old property in advance of the sale, or complete the trade and then refinance the new property to take the cash out. In both cases, the additional financing must be independent from the exchange. Refinancing after the trade is generally preferable from a tax perspective. And there are ways to structure the refinancing without incurring additional fees.

How much gain do I have if I trade down?

The way to calculate this is first to figure out what the gain would have been on an outright sale. On an exchange, one can never have more gain than that. Then look to the amount of cash that was not rolled over, or the amount by which the purchase price of the new property is less than the selling of the old property. This will be the so-called “boot.” The gain is the lesser of the gain that one would have had on an outright sale or the amount of boot. For example, say that on an outright sale, one would have had $50,000 of gain. On the exchange, there was $10,000 of cash that was not reinvested. The first $10,000 of gain is subject to tax. It is not one-fifth of the gain. The boot is taxed dollar for dollar off the top, subject to the limitation that there cannot be more exchange gain than on an outright sale.

What is a year-end push?

If the taxpayer sells property and deposits the exchange proceeds with a qualified intermediary in the last 179 days of the year and has a bona fide intent of doing a like-kind exchange, but the exchange does not close in the succeeding year (the 180th day must fall in the succeeding year), the gain is deferred into the succeeding year. As noted, one must have a bona fide intent to do the exchange; there are steps that a taxpayer can take with his attorney to prove up that intent in advance.

What about partnership exchanges?

One cannot exchange partnership interests, even if the partnerships own real estate. (Of course the partnership can do an exchange itself.) The same prohibition applies to interests in limited liability companies and corporations. But in the case of limited liability companies and partnerships, there are ways to structure ownership with multiple parties as co-tenancies, preserving the notion of individual ownership and avoiding partnership classification. There are special tax elections that certain partnerships and limited liability companies can make in order not to be treated as a such for income tax purposes (even if they are valid entities for state law purposes). There are ways of cashing out non-trading partners from a partnership to allow the trading partners to remain in the partnership and accomplish their sale. All of these transactions require careful structuring in advance of a transaction and reference should be made to Revenue Procedure 2002-22.

What about exchanges with related parties?

One can sell old property to a related person and still do an exchange. One cannot purchase replacement property from a related person, even if the related person pays tax.

What about non-real estate?

What a lot of people do not know is that one can exchange many types of non-real property held for investment or used in a business. For example, a manufacturing company can sell its delivery vehicles as part of a like-kind exchange and avoid the depreciation recapture. For non-real property, the “like-kind requirement” is interpreted much more narrowly. It must be essentially the same type of asset purchased as sold. A dump truck for a dump truck, a bakery oven for a bakery oven, etc. Goodwill is not exchangeable (but franchise rights and certain types of licenses can be exchanged). Personal use property is not exchangeable.

What about stocks and bonds?

Stocks, bonds, notes, partnership interests, limited liability company interests, interests in trusts (except for land trusts) and similar types of intangibles are not exchangeable.